Accuracy - the term we all human beings (and even machines) are aware of. We know it when something means “accurate”. Accuracy is the ability of a system to correctly identify what it is supposed to be. It is the property of a system (and model) that correctly labels something.

When the accuracy is 95 percent, it clearly implies that out of 100 inputs given to the model (the system), it correcly identifies 95 of them, remaining 5 being inferred as “incorrect”.

So far so good right? > Hell, yeah! I know what accuracy means**.

Well, what can I say? You got me there. Now consider this. The system is a disease identifier like cancer detection.

Now, what does 95 percent accuracy mean here? Out of 100 people, 95 percent of them are identified correctly as either

being non-cancerous or cancerous.

That sounds familiar. But what if remaining 5 folks had cancer? Well! That doesn’t sound quite good.

Which medical facility wants a system that is 95 percent accurate but fails to identify

acutal cancer?

accuracy = (number of patients diagnosed correctly) / (total number of patients)

Now, we are onto something here. In a very sensitive system like in the example, labelling something incorrectly can result in a matter of life and death. In such systems, the skewness of data (there are far more people with no cancer than the ones who have) makes it difficult to evaluate the system. That’s why accuracy is not an “accurate” metric where we have to correctly identify the data that occur rare.

Similarly, we can’t just make the system tag every people encounter to have cancer. In this case, people with cancer are identified, but rest of the people are in trouble in terms of money, mental health and whole other shit. :(

Meet The Conjugate Twins: Recall and Precision

We focus on the rare portion of data. What is it we are trying to identify?

- the person has cancer?

- the person is a terrorist (let’s not dive into philosophical aspect of this) ?

- the person is a criminal?

- my automatic house door detecting people as “not a Nish”?

- …

Let’s call them positive cases(from the system’s viewpoint).

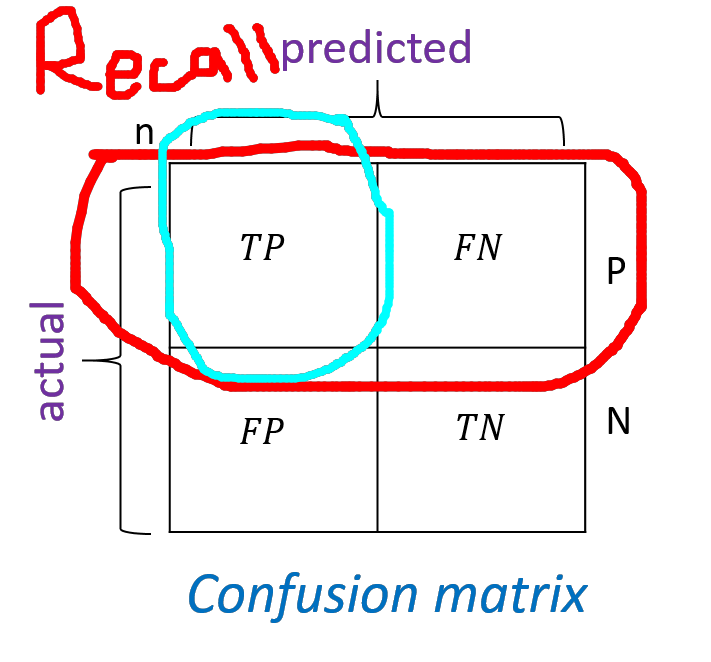

Recall

Recall is the number of positive cases identified correctly by the system out of the total positive cases.

Mathematically,

recall = (true positives) / (true positives + false negatives)

Terminology

true positive ==> expected case is positive and prediction is also positive

true negative ==> expected case is negative and prediction is also negative

false positive ==> expected case is negative but prediction is positive

false negative ==> expected case is positive but prediction is negative

So, recall simply is the ability of the system to recall the truthness of the original data. How much can you recall the things you have learnt in high school? It’s like that. You know you have learnt a nasty formula in mathematics, but is it correct? Here, “identiying a mathematical formula” can be taken a positive case.

intuitively,

recall = (cancer patients identified as having cancer) / (total number of patients having cancer)

Now, initially our thought process can align to maximize Recall towards 1. But is it sound? Do we have perfect predictor? No! Although the system has identified people with cancer with cancer, the chances are it has also tagged other people with cancer too. We can’t go on and tag every people as having cancer. There is a tradeoff between recalling and being precise.

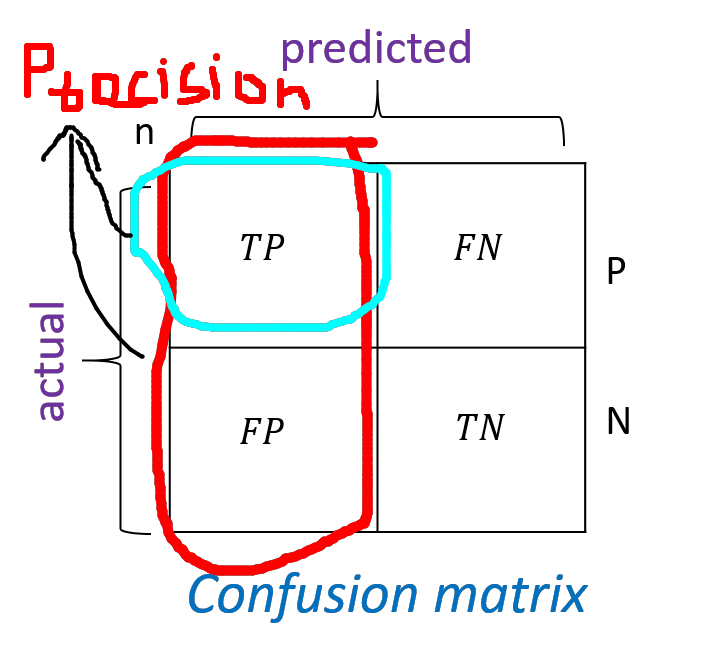

Precision

Out of all the cases that the system says ‘positive’, how many are actually ‘positive’ ? That is how precise is the system?

Mathematically,

precision = (true positives) / (true positives + false positives)

Intuitively,

precision = (cancer patients identified as having cancer) / (total number of people the system tags with 'having cancer' )

Again, here if we try to maximize precision, we might miss the cases of false negatives - the case where people with actual cancer being tagged as not having cancer. That’s a tradeoff.

Meet The Guru: F1 Score

Individually, precision and recall didn’t do well when maximizing the metric. So, what’s the plan?

Let’s try something.

Arithmetic Mean

Suppose our metric is G that incorporates both precision and recall.

Let,

G = (P + R) / 2

Seems fair!

Let, P=1 and R=0. We have, G=0.5. Well, that’s awkward. Despite the fact that the system is not recalling,

the average is pointing that it is indeed a mild predictor. Same is true when roles of P and R are reversed.

But, what if we multiplied P and R?

Let,

G = P * R

Considering above case, we have G=0. Seems fair enough.

F1

Instead of taking Arithmetic average, we can use a metric that multiplies both precision and recall. F1 score is one of such metric. It is a harmonic mean that tries to get compensation for extreme values.

Mathematically,

F1 = 2 * Precision * Recall / (Precision + Recall)

Cases:

P=1, R=0.1 ==> F1 is 0.18

P=1, R=0.5 ==> F1 is 0.66

P=1, R=1 ==> F1 is 1

P=0.1, R=1 ==> F1 is 0.18

P=0.5, R=1 ==> F1 is 0.66

So, F1 score tries to penalize when there are disparities (or greater gap) between precision and recall.

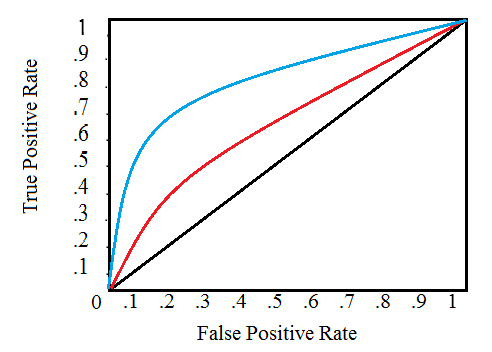

ROC: Beyond Precision and Recall

Receiver Operating Characteristic is the plot between True Positive Rate (TPR) and False Positive Rate (FPR).

It is used to identify the threshold for a binary classifier - that is beyond what point should the classification be 1

or below which the classification is labelled 0. ROC plot is used to identify such threshold which is commonly referred to as

Discrimination Threshold.

Intuitively, say we are to identify a tumour as being “non-cancerous” or “cancerous”. We build a classifier that outputs in the range of (0, 1) - 0 being “non-cancerous” and 1 being “cancerous”. So, upto which value in that range, is the cell “non-cancerous”? We can set it experimentally (hit and trial) and might have “seemingly working” classifier. But, that’s not good. We have manually set the threshold. In such case, we use the plot of ROC and identify a single value beyond which the metric TPR and FPR falls. This is the point at which classifier is “just” able to identify tumour “correctly”. Actually, this is just an over simplification of the area under the curve. (Look at the ‘Further Read’ section)

When is the time to switch from Accuracy to other metric?

Use Accuracy whenever it doesn’t matter if you miss some of the Positive cases:

- cat vs dog

- hot-dog?

- sentiment analysis

- chocolate classification

- text generation

But the usage varies based on actual problem space. If you think failing to identiy a chocolate type in a supermart sometimes

doesn’t harm, just stick to accuracy. Else find other metrics to evaluate the classifier.

As seen in this SO’s Post

always try to get statistics of your training dataset - its skewness, the distribution, etc.

And see if you need to go beyond.

In cases like text generation there isn’t any metric to actually know what the text is supposed to be since the whole idea is based on probabilities of occurence of next token (character/word/ngram) which is based on frequency distribution. For this problem, to what ‘real output’ can you compare to measure if the model is doing fine? One metric might be to use Markov Chain and calculate probability of the generated text as a metric.

Similarly, in a system like linear regression that tries to predict real values (not probabilities), accuracy doesn’t seem to make sense. In such case metrics like Mean Squared Error (MSE) might give clear idea on how much “lossy” the system’s output is.

There are more metrics beyond what traditionally are known. Sometimes, it’s even possible to invent your own metric that will make sense of the input and output. Choose wisely. Don’t hesitate to experiment with your system.

Side Note: Please, don’t forget to share this post if you think it makes sense

Further Reads

- The Relationship between Precision-Recall and ROC Curves

- The Class Imbalance Problem

- Difference between ROC Curve adn PR Curve

- Confusion Matrix

- Metrics To Evaluate ML Models